It’s the night before March for Our Lives, and Lafayette Square teems with anti-gun protesters, a few counter-protesters, and Washington, D.C. tourists. Two teenagers are posted in front of the White House, youthful sentries braving the cold.

“I came from Douglas to protest for my 17 friends who can’t!!!” their construction paper-and-marker protest sign reads. The first names of the teenagers and staff members killed in the Parkland, Florida school shooting are scattered throughout in multi-colored scribbles, some accentuated with small red hearts. The girl’s makeup is smudged; she appears to have been crying.

“We were making Valentine’s Day cards, and the next second we were being shot at, literally dodging bullets,” the 16-year-old Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School junior, Randi Patregnani, says, clutching a Starbucks cup.

It was just another Valentine’s Day. Patregnani was crafting heart-shaped cards out of construction paper for her friends, classmates, and favorite teachers. While the rest of the nation’s students celebrated a day of love, the students of MSD fought to live. In only a few minutes, Patregnani’s school day plunged into the epicenter of the national gun debate, making the school a household name, like Columbine, Sandy Hook, and Virginia Tech. Overnight, the shooting made public figures out of teenagers who should have been worrying about school and getting ready for college.

And so Patregnani finds herself in the nation’s capital along with her classmates, meeting with senators and joining thousands in protest. It is here that she makes her plea for change.

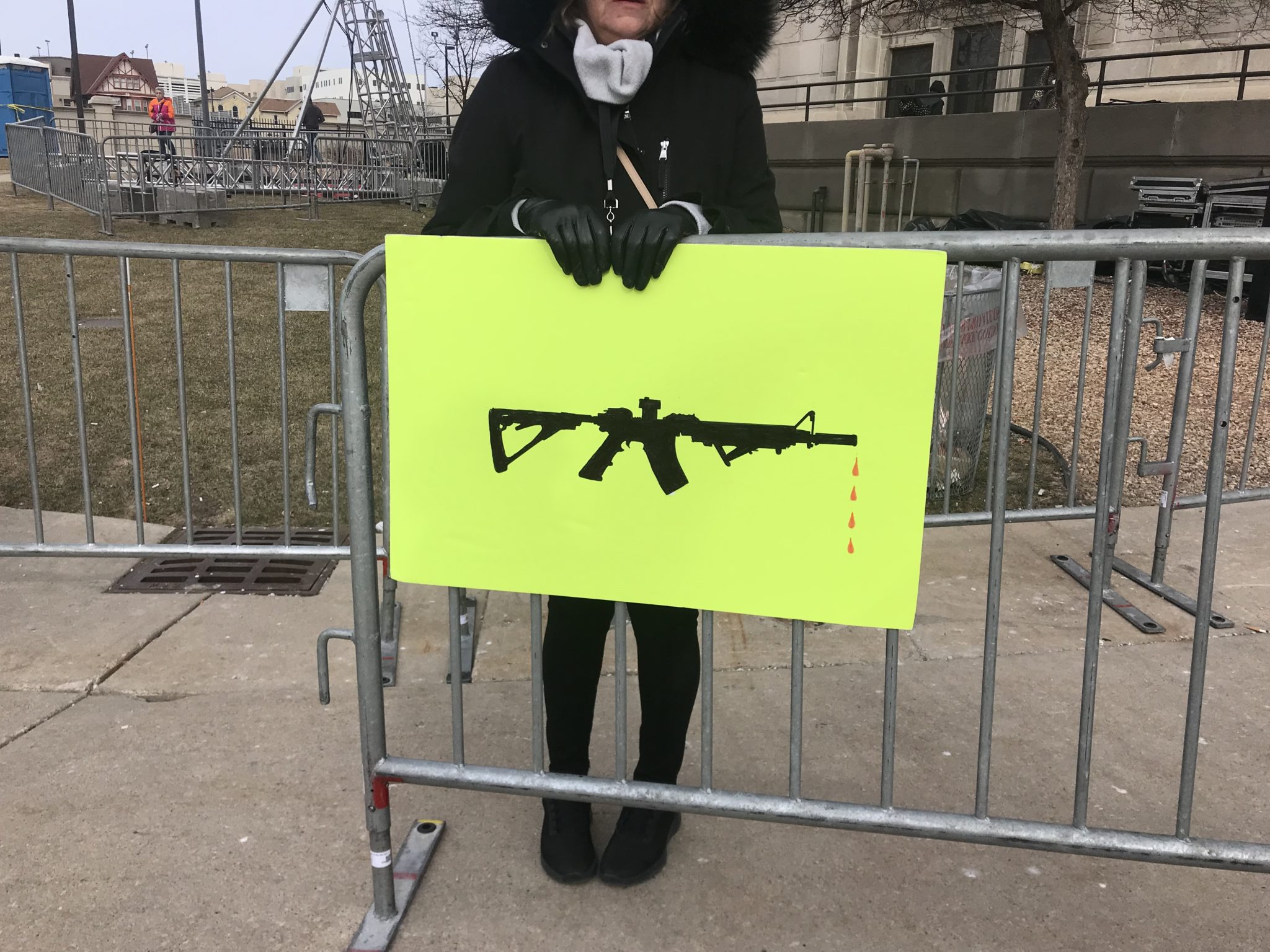

“Nobody needs assault rifles. You really don’t. They were made for killing people,” says Patregnani. “…We’re going to prom. You don’t need that.”

Just before dismissal, 19-year-old Nikolas Cruz, a former MSD student with a pattern of troubled behavior, is accused of entering the Parkland school building with a legally-purchased AR-15. In six minutes and 20 seconds, Cruz would allegedly kill 17 and mobilize a movement. The children of Sandy Hook Elementary School were too young to lead it. The teenagers of Stoneman Douglas, with their social media savvy, are ready. Rob Cox, a Reuters editor hosting a National Press Club gun policy event, labels them “Generation Lockdown,” young people who’ve never known what it’s like to not be afraid at school.

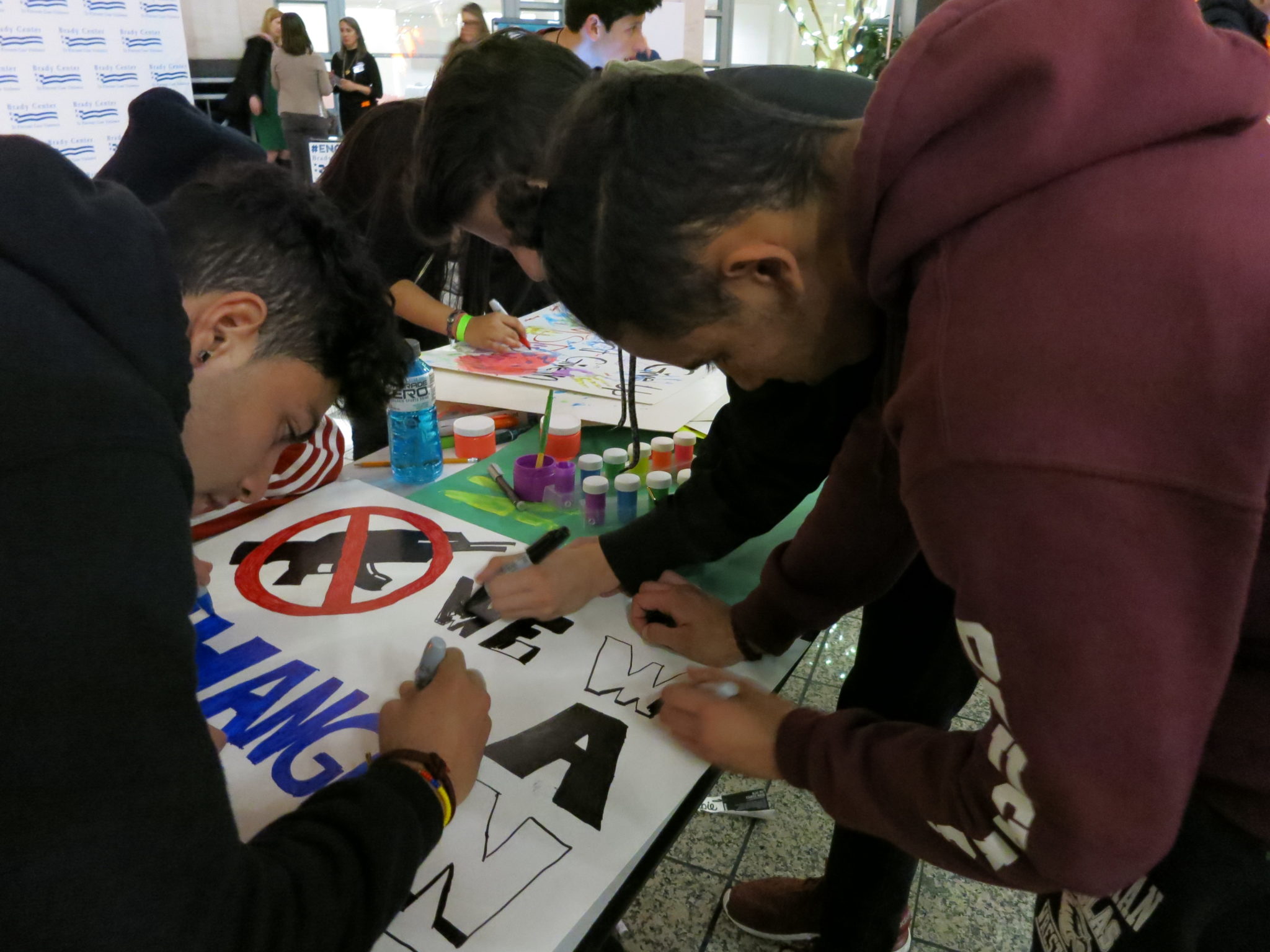

While Patregnani stood outside the White House with the sign clenched in her hands, some of her classmates gathered at the National Education Association building down the street with students from around the nation. They were making more signs in preparation for the march. Some displayed slogans such as “SCHOOLS NOT WARZONES,” “Protect Kids Not Guns,” and “NEVER AGAIN.” Several students from Stoneman Douglas worked together on a hand-drawn sign that read: “WE WANT CHANGE” in large letters, with a “no” symbol over an assault rifle.

Enlarge

Robyn Schwartz was at the poster-making event with her son, another MSD student. Schwartz lives right behind the school, and, on the day of the shooting, she was there within minutes, just in time to witness blood-soaked students streaming out. Her son escaped unscathed, although he texted her frantically from a hiding place, but one of her neighbors was not so lucky.

“Assault weapons…why are they out there?” says Schwartz. “Who has a need for them? They’re not hunting with them. There’s no need for assault weapons.”

She pauses to contemplate whether this movement will accomplish policy changes that others did not. “They’re teenagers, not 5-year-olds; they’re young adults, they have a voice. That’s why it’s different,” she concludes.

Diverse voices

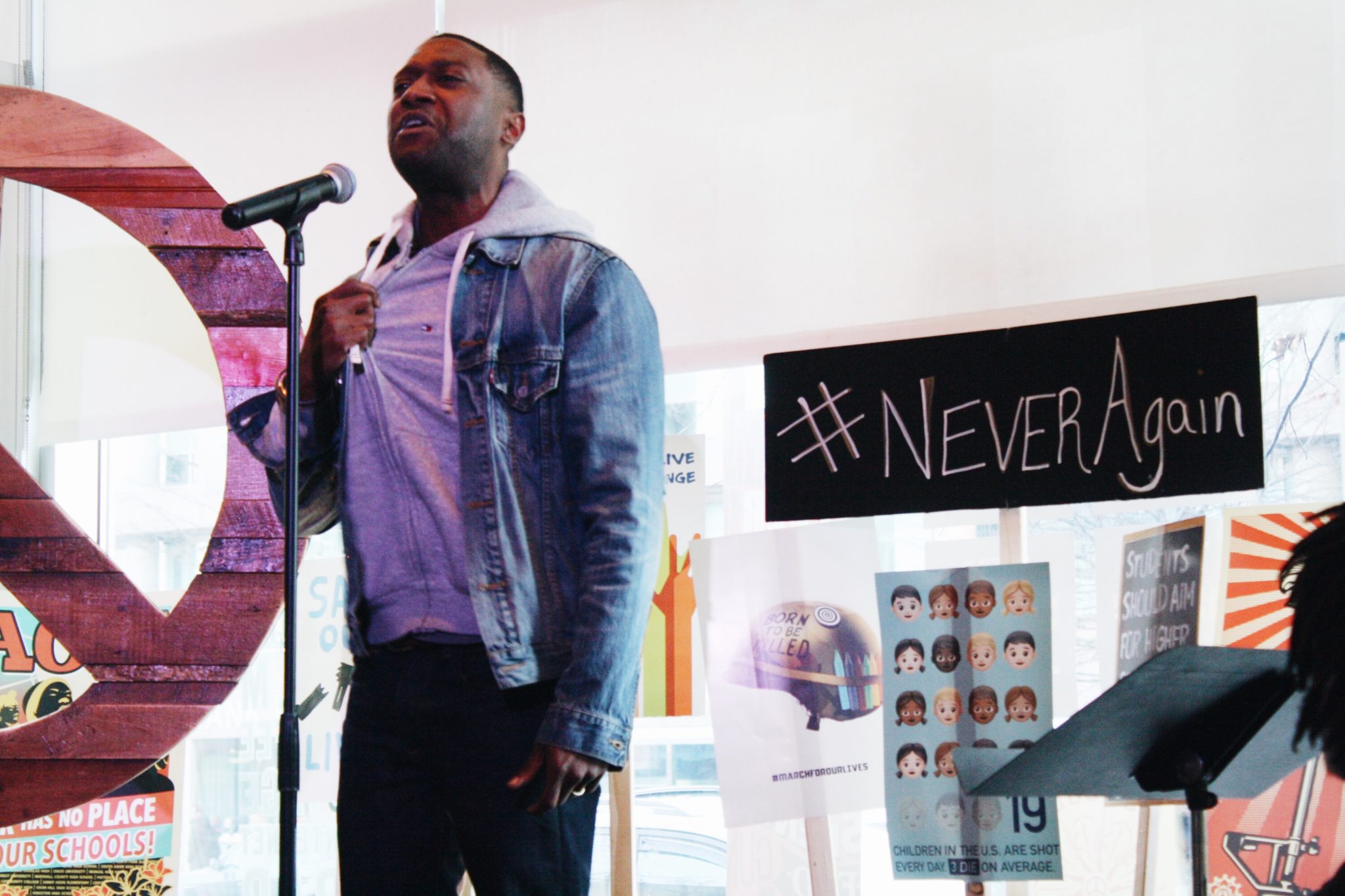

Across town, on 14th and V street, at a restaurant called Busboys and Poets, more than a dozen young activists ask many of the same questions. They are performing spoken-word pieces at an event called Louder Than A Gun – Open Mic for Our Lives. The pieces are inspired by gun violence, school shootings, racism, sexism and more. The carnage in the cities drives much of their prose, with an overlay of anger toward the police. The crowd is mostly African-American, although they’ve been joined by the Hollywood celebrities Kevin Bacon and Kyra Sedgwick.

“We need to make noise like we’re saving lives tomorrow,” event host Joseph Green says. “We need to make noise like we’re sending a message to the people who have been making decisions that have cost us our lives for years.”

Washington D.C. native Tony Keith, in his final year of a PhD program focusing on spoken word poetry’s effects on student engagement, performs a piece he wrote after the Missouri police shooting of Michael Brown.

“There’s a correlation between the way we treat money and the way we treat people,” Keith says in the piece. “…Now, blood-covered brown men, hands up, holes in their backs, racism is making withdrawals, y’all.”

Enlarge

Photo: Elizabeth Sloan

These artistic demonstrations express feelings and encourage change. Although the approach may differ somewhat, the poster making and poetry slam represent an intersection between urban gun violence and mass shootings in schools.

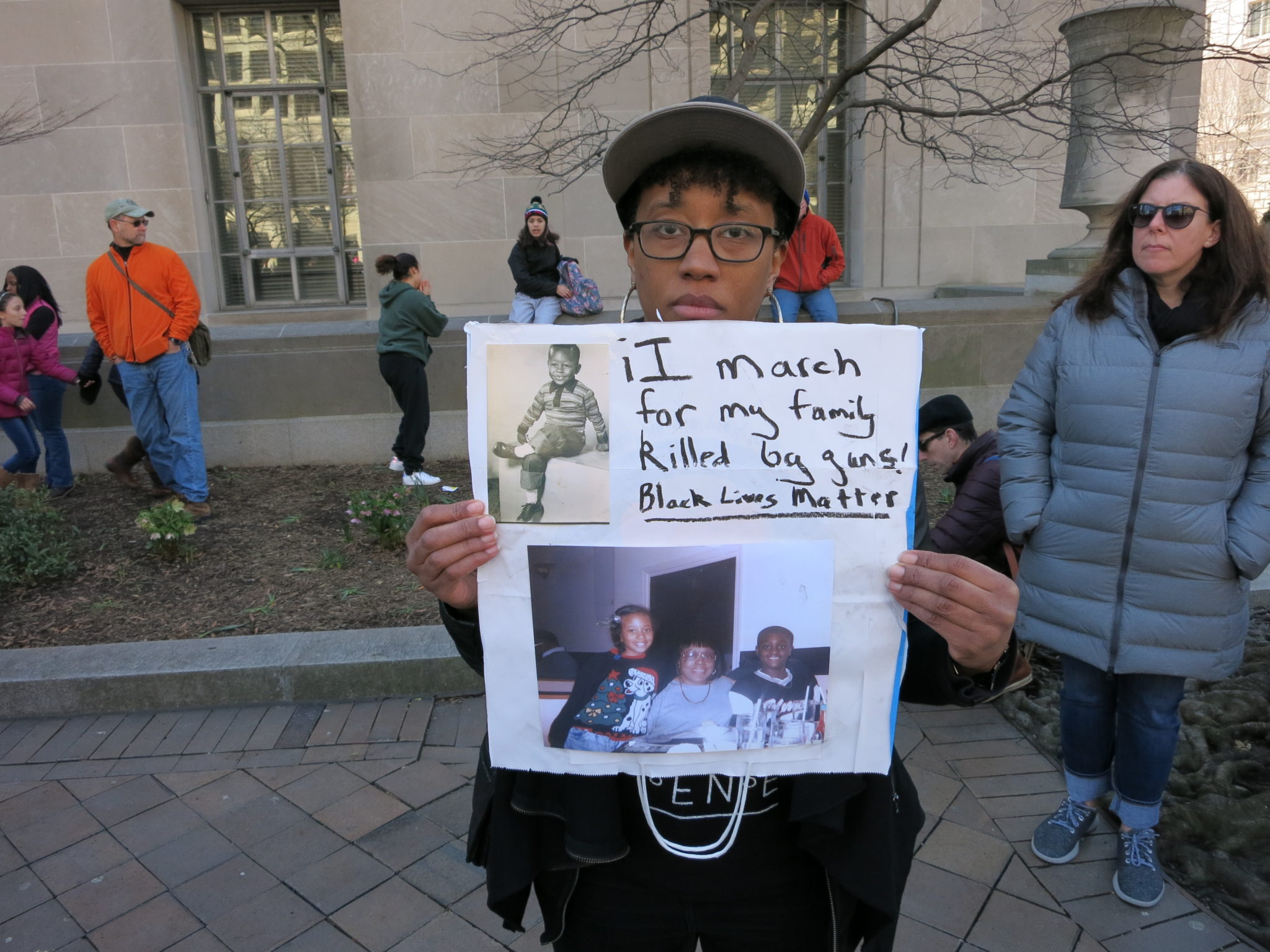

The following morning, at a Rally for D.C. Lives that eventually flowed into the larger gun control march, Thurgood Marshall Academy student Lauryn Renford shared her story of loss through tear-soaked testimony. She described the relationship she had with her boyfriend Zaire Kelly, who was shot and killed on his way home from a D.C. school only a year ago and left unable to apply to college with her. His story stopped entirely, despite being filled with potential. Some marchers wore Black Lives Matter pins or slogans.

According to the Metropolitan Police Department’s 2016 Annual Report, there were 135 homicides in Washington D.C., with firearms accounting for 77 percent of the murder weapons. Some see a racial disparity in the news coverage.

“We finally have victims who have, because of their privilege, received a national platform because they’re white,” says Jamira Burley, senior adviser for the Community Justice Reform Coalition, during a National Press Club panel discussion on gun control. “We need to see all human death as a problem.”

Burley also notes a difference, though. She praised the Parkland students for being more inclusive than previous generations.

“We have to work together,” says Burley. “We have to find ways and opportunities for us to collaborate and to create pathways for all young people to sit at the table together and create comprehensive solutions.”

Enlarge

The Black Lives Matter representatives soon blended into D.C. streets packed with hundreds of thousands of others from all walks of life. Mothers pushed newborn babies in strollers, high schoolers carried signs and cameras and held hands with their friends to avoid getting separated, and old men and women – some of whom recalled past protest movements – clipped new pins to their worn coats. People shared their experiences with gun violence. The shouts called for Americans to “vote them out,” and “never again.” Posters scraped the sky.

However, the demonstration of seeming unity obscures the fact that America remains a country riven with disagreement over guns.

Enlarge

Easily missed in the sea of marchers, three men stood, largely silently, outside the Trump International Hotel to, in their words, show that a lot of Americans do support the Second Amendment. One wore a red “Make America Great Again” cap. Here they are outnumbered, protected by police, and mostly ignored in favor of the louder, more confrontational anti-abortion counter protesters, who get in heated verbal clashes with anti-gun marchers. Many signs drew attention to the financial contributions the NRA contributed to different politicians and some singled out Trump. Indeed, the NRA spent more than $52 million in the 2016 election cycle, with $30.3 million of that going towards Trump alone.

“Freedom of Speech and Assembly Aren’t Guaranteed by the First Amendment, They’re Guaranteed by the Second!” Colin Valentine’s sign read. One of the other two men, who would only give his name as Jean, held a white board with the phrase, “Gun grabbers only care about lives when guns are involved,” scrawled across it.

While they stood together in defense of the Second Amendment, the overlap of their views on gun control didn’t extend too far beyond that. Valentine believed there should be some regulations and didn’t think his views differed too much from the protesters he positioned himself against.

Enlarge

“I think that there’s a bunch of solutions and a lot of common ground to be had. And I think a lot of people out here protesting would probably agree with some of this,” said Valentine. “Part of it is making sure that we prosecute gun crime more strictly and enforce the laws on the book better than we have.”

Jean, on the other hand, identified as a libertarian and referred to his home state as the “Soviet Socialist Republic of Maryland.”

“I personally don’t believe any gun control has been effective at reducing violence. I don’t really make the distinction between violence and gun violence. It doesn’t matter how people die, it just matters that they’re dying,” said Jean.

For Jean, the solution is in more gun ownership rather than increased regulation.

“I see gun ownership like vaccination; the more people that have it, the less people die.”

Jacob Kenworthy, 17, was visiting D.C. from Indiana for a school trip that just so happened to coincide with the march. Standing at the Lincoln Memorial, he proudly sported a sweatshirt that displayed USA on one side and “Trump 45” on the back.

“I am a Trump supporter,” he said. “He is our president after all, so I mean you have to support him.”

Although Kenworthy said he believed in gun ownership, he conceded that maybe the age requirement could be raised.

As for the marchers, he added, “It’s their right to protest. I don’t have anything against them protesting.”

Exploding gun sales

One study by an University of Maryland professor into the March for Our Lives protesters in Washington D.C. found that those marching were largely Hillary Clinton supporters and older than the youths who dominated the media attention. However, the study also found more moderates and people new to protests when compared to other marches. Polls after the Florida school shooting showed an uptick in support for gun control, with two-thirds of Americans wanting tougher policies, even as the political debate remains largely stalled, and the NRA unswerving.

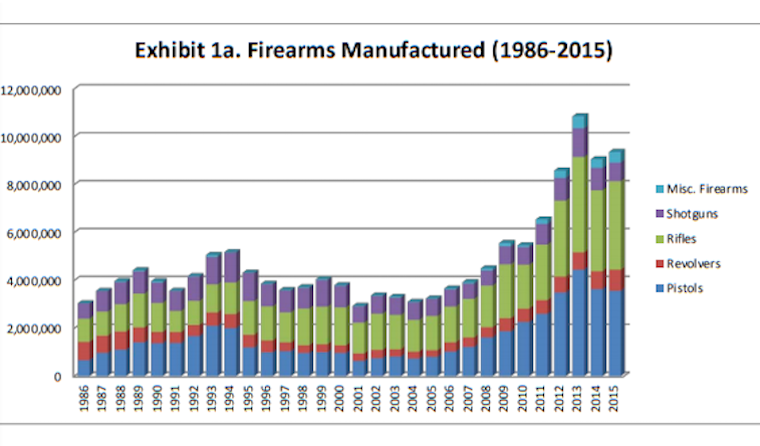

Will this movement be different? That remains to be seen, but the United States has witnessed such outcries before, and they didn’t cease its historic love affair with firearms. If you thought the debates surrounding Columbine or Sandy Hook stopped Americans from buying guns, think again.

Enlarge

More firearms are being manufactured in recent years, with more than 9 million guns produced in 2015 alone, according to the most recent ATF statistics. The number of guns made in America tripled since 1986. The number grew after Columbine, and it grew after Sandy Hook. The ATF reported a 43-percent increase in firearms manufacturing in the past five years in its 2017 report, which ends with 2015 data, the most recent available.

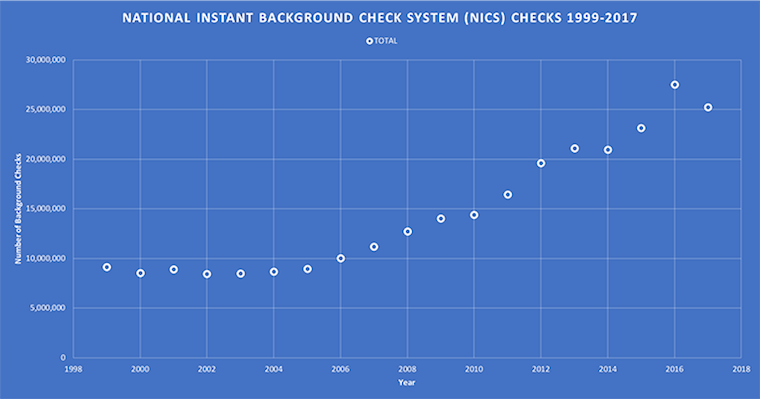

And those numbers are met by demand. The National Instant Background Check System, or NICS, provides some insight into gun sales over the years, despite some research into gun control being limited by the Dickey Amendment, which mandated that “none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” NICS was launched in 1998 by the FBI and requires all federally-licensed gun sellers to determine whether or not a potential buyer is eligible. However, while NICS is a good indicator of these types of sales, the data is limited because some states, such as Virginia, do not require background checks for private gun sales.

Enlarge

The number of NICS background checks has skyrocketed in the last two decades, with the number of NICS checks in 2017 more than triple the amount in 1999.

Enlarge

A 2016 study from Northeastern University estimated that the number of privately owned guns grew by over 70 million to around 265 million from 1994 to 2015, despite the number of gun owners only increasing by approximately 10 million in that same period. In fact, the study found that 8 percent of gun owners own 10 or more guns, and these owners account for 40 percent of privately owned guns.

Indeed, polls have indicated that some gun owners may be stockpiling weapons because they’ve documented declining gun ownership rates at a time of booming sales and manufacturing. While some areas have passed strict gun control laws, the patchwork nature of them throughout the country makes it easy for firearms to be purchased and cross state lines.

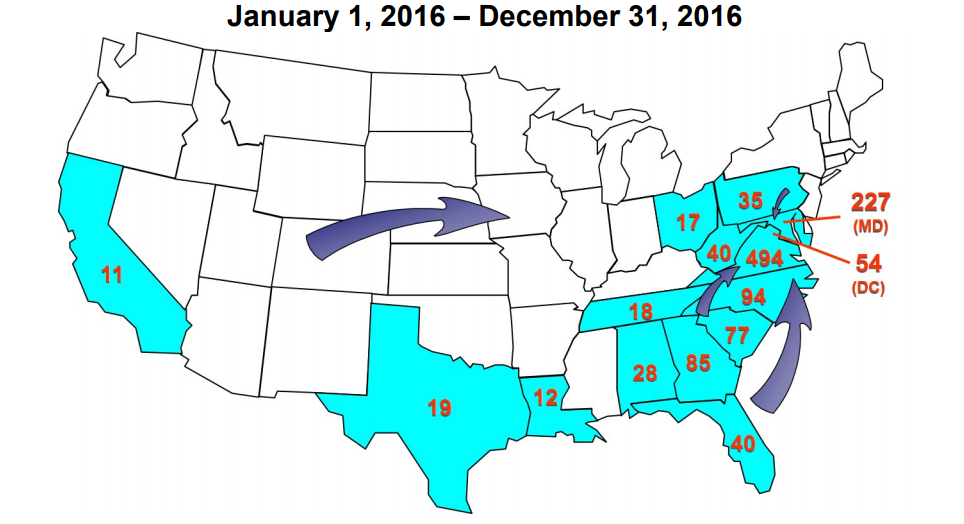

“You should be proud that your council of the District of Columbia has moved on some of the toughest and smartest gun legislation in the United States of America,” DC Mayor Muriel Bowser told a cheering crowd on the morning of the gun control march. “But our laws don’t help us if Virginia doesn’t pass common sense gun laws, if Maryland doesn’t pass common sense gun laws, and their illegal guns come into our city.”

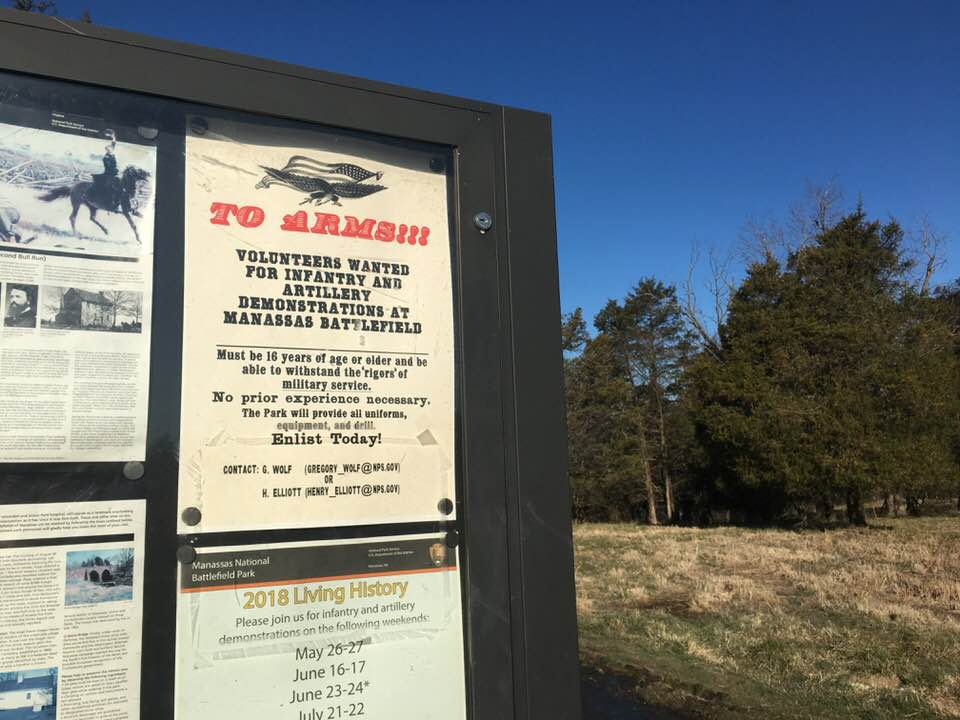

As hundreds of thousands marched in D.C. and even more in sibling marches in cities across the nation, another side of America spent their Saturday much differently. According to one website, there were at least 43 gun shows on the same day throughout the United States. At least three gun shows in adjacent Virginia occurred simultaneously with the March for Our Lives – one a mere 32 miles away, in Manassas, site of one of the country’s bloodiest battles in the Civil War, a conflict that helped forge the American gun industry. That conflict ushered in a “technical revolution in weaponry,” according to Civil War.org. (Remington, a gun manufacturer whose weaponry dates to the Civil War, recently declared bankruptcy.)

Enlarge

To more fully understand the nation’s gun control debate, it’s necessary to traverse the ideological and cultural divide that stands between D.C. and Virginia, and, symbolically through them, the rest of the country. It’s a mere 35-minute drive from the White House gates, where a woman has splashed herself in red paint and wears a devil’s outfit, claiming she’s saved a special place you-know-where for the NRA, to the former heart of the confederacy where support for gun rights remains visible and strong.

Emma Gonzalez spoke for six minutes and 20 seconds in Washington D.C., pausing in silence, to show how quickly 17 young lives were taken. Just 32 miles away, though, men outfitted in NRA caps and patches bought, sold and collected guns and war memorabilia.

In Virginia, you can find people who proudly boast that they “love guns” and who carry them openly while shopping in the Dollar General store, although many say they are afraid confiscation is imminent and comment that they feel severely mistreated by the media. However, although those interviewed remained steadfast in what they label “responsible gun ownership” and their support for the Second Amendment, time and again, they also voiced support for at least incremental change. The man running a Manassas, Virginia gun show is OK with universal background checks, for example. A man working in a Virginia gun store is OK with raising the age limit for purchasing firearms, in another.

Enlarge

Here, gun ownership is a tradition often centering around individual liberties and sportsmanship.

“I’ve been an outdoorsman for about 40 years now,” says Mike Bowman, who lives on a 200-acre property and whose family has been in Virginia for as long as he can remember. The owner of several businesses, Bowman, who is also a coach, painted “Don’t Tread on Me” next to the American flag on his barn. He also says he owns 60 guns, including an AR-15 which he uses for target shooting, and voted for Trump. He still supports the president because he thinks he’s brought jobs to an area that needs more of them.

“I think the appreciation of the outdoors is going by the wayside. You know, because your newer generation today, they have parents who are scared of guns and ammunition,” Bowman says. Being a good gun owner involves common sense, values and respect, in Bowman’s opinion.

“I keep all my guns in a safe, and there’s just two people who know the combination and that’s me and my wife,” he adds. “I don’t leave guns just laying around loaded. Now, I do carry a concealed weapons permit, because I do have that.”

Bowman, an avid hunter, believes mental health treatment is the key concern when it comes to stopping school shootings.

“People who don’t like guns don’t like guns,” he concludes. “They don’t like hunting, they don’t like killing, and they don’t like anything about it.”

Two Americas?

The small gun store nestled on a quiet block in Arlington, Virginia, only about 10-15 minutes from the White House, has a door that opens with a handgun handle. Its website touts that it sells “high-end sporting and self defense arms and accessories.” Inside, the store bustles with activity only a couple hours after the D.C. gun control march. The diverse clientele strolling through the shop consisted of customers representing both genders and multiple ethnic backgrounds. To buy a firearm that is not a handgun from a licensed dealer in Virginia, you must be 18. You must be 21 to purchase a handgun. The state allows open and concealed carry, and it does not require background checks on private sales.

Republicans control the state’s General Assembly, thus giving them the ability to block gun control proposals. However, one local newspaper reports that gun control advocates are spending more in recent years than those opposed to it.

In the gun store, customers came in steadily. Chris Chen, 25, a Georgetown University graduate student with dreams of working for the Department of Defense or Homeland Security, commented on the firearm nomenclature that the media often get wrong.

“I think a lot of journalists, you know and don’t take this personally, but that’s just not what they specialize in, and it’s hard for them. A job in journalism means fair balance,” Chen says. He works at the store.

Speaking only as an individual and not on behalf of the gun shop, he defined words like “semi” versus “fully automatic,” “clips,” and “magazines,” and explained the AR-15, which has been demonized on signs throughout D.C. Chen, who wore a handgun strapped to his leg, is originally from California, where his Thai immigrant father works as a trauma doctor and helped inspire his affection for firearms.

Enlarge

The walls were lined with weapons, each carrying the weight and appearance of a gun set to fire. Chen pulled the AR-15 down off the wall and described the ways in which guns can be modified to fit gun regulations in states that may have stricter laws in place, and he referred specifically to California. Gun purchasers are diverse, and more LGBTQ individuals purchased firearms after the Pulse massacre in Orlando, he said.

“So I am a huge history nerd. I’ve been into guns since I was about 11-years-old, and I could tell you everything about this gun right here,” Chen motioned to a 100-year-old Russian weapon hanging on the wall. “With the old guns, it’s like they all tell a story and trying to figure that out is like your own kind of history project.”

Chen said that there were three gun shows he knew of going on in the area; he pulled out his phone and showed the names and locations and even advised which show would likely be the best to attend.

Virginia is home to the National Rifle Association, which developed from a rifle shooting club founded by two Union veterans in New York in 1871 into a political force. Some say it protects the Constitution, while others say it’s an impediment to reasonable regulation.

Gun supporters say the industry creates jobs and funnels millions of dollars into the economy.

However, Virginia is also the site of several notorious mass shootings, including Virginia Tech and the Congressional baseball practice. It’s the state where a reporter was gunned down on live TV. Virginia is where John Wilkes Booth fled after gunning down Abraham Lincoln in a theater in D.C. Manassas is where George Zimmerman was raised before he moved to Florida and shot Trayvon Martin. Heather Heyer, a protester, was killed during a neo-Nazi rally in Charlottesville.

In Manassas, Virginia, at the site of the First Battle of Bull Run, and not far from Saturday’s gun show, New York transplant Robert Tringali is going for a morning stroll.

Enlarge

“They’re very, very pro-gun out here, extremely pro-gun,” says Tringali, a New York native who spent seven years living in Manassas, of Virginians. “It’s kind of an NRA thing, but after a mass shooting there’s always a day or two of silence and then the inevitable is thoughts and prayers. That’s kind of the attitude out here. This Virginia is never going to change how they feel about guns.”

Virginia has some of the most relaxed gun laws in the country and quite possibly could be called the birthplace of the American relationship with guns and the 2nd Amendment, which famously reads, “A well regulated militia being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms shall not be infringed.” Most guns sold in Washington, D.C. and traced by the ATF are from Virginia.

For example, in 2016, the most recent year available, 494 guns of the 1,969 traced from DC were traced back to Virginia, the most of any source, with Maryland a distant second. (In contrast, most guns traced in Virginia, Florida and Wisconsin that year came from within those same states.) Virginia itself had 8,449 traced guns that year, the ATF reports, mostly pistols. Traced guns are often, but not always, used in crimes. Nine states were source states for a larger number of firearms traced nationally than Virginia, though, with California and Texas leading the way.

In 2017, only three states had more registered firearms than Virginia’s 307,822: California, Texas, and Florida, federal statistics show.

Enlarge

It should come as little surprise when one looks at Virginia’s history. It is a state both birthed and shaped by the principles of the Second Amendment. Seventeen of the founding fathers called Virginia home as they led an armed insurrection against what they saw as a tyrannical government. Membership in militias and gun ownership was compulsory for white males in the Colonies (but punishable by death for Native Americans). However, Cornell University Professor Robert Spitzer argued in a research study that regulations on firearms also were prevalent in the nation’s earliest days. The nation’s second armory was erected in Harpers Ferry, Virginia, in 1799.

This history remains visible in the landscape. One ramshackle garage bears a sign festooned with a cannon and the words “come and take it.” On the drive into Manassas, specifically Centerville Road, sits another small gun store with a sign that was larger than its storefront. In the dark of night, the words Dominion Arms, in blood red stencil font, shine bright. The front door is peppered with stickers stating “Guns Save Lives,” “Don’t Tread on my Gun Rights,” “United States Marines,” and “Win the War.”

In Manassas, one will find history embedded in the once bloody soil of Bull Run (or “Battle of Manassas” if you aren’t a “Yankee”), painted on the sides of sheds and waving on flagpoles. A Confederate flag flaps in the wind below the American flag, a grizzled old man at a gun show proudly wears the full Confederate uniform and displays a gun used at Gettysburg, and the monument in town to Confederate General Stonewall Jackson was defaced with the word “DEAD!” in gold spray paint but still stands. There’s a Confederate Court. Children attend Stonewall Jackson High School. Mike Bowman’s “don’t tread on me” slogan, painted on his barn, is not the only one.

Enlarge

“The don’t tread on me painting? Well, I don’t know what it means really,” said Bowman in reference to the large painting. “I guess to me it’s like, don’t hate on me. Don’t judge me. You know?”

The Gadsden Flag, commonly known for its trademark phrase “DON’T TREAD ON ME,” dates back to 1751 when The Pennsylvania Gazette wrote a resentful article in protest of Britain’s practice of shipping convicts to America, and suggested sending a cargo of rattlesnakes to the nobleman’s gardens. In 1754, the paper printed a dismembered snake with the words “Join or Die.” By 1774, the segments of the snake grew together, and it was paired with a new motto: “United Now Alive and Free Firm on this Basis Liberty Shall Stand and Thus Supported Ever Bless Our Land Till Time Becomes Eternity.” By 1776, the Continental Navy displayed this flag, or one of its variations, throughout the Revolutionary War.

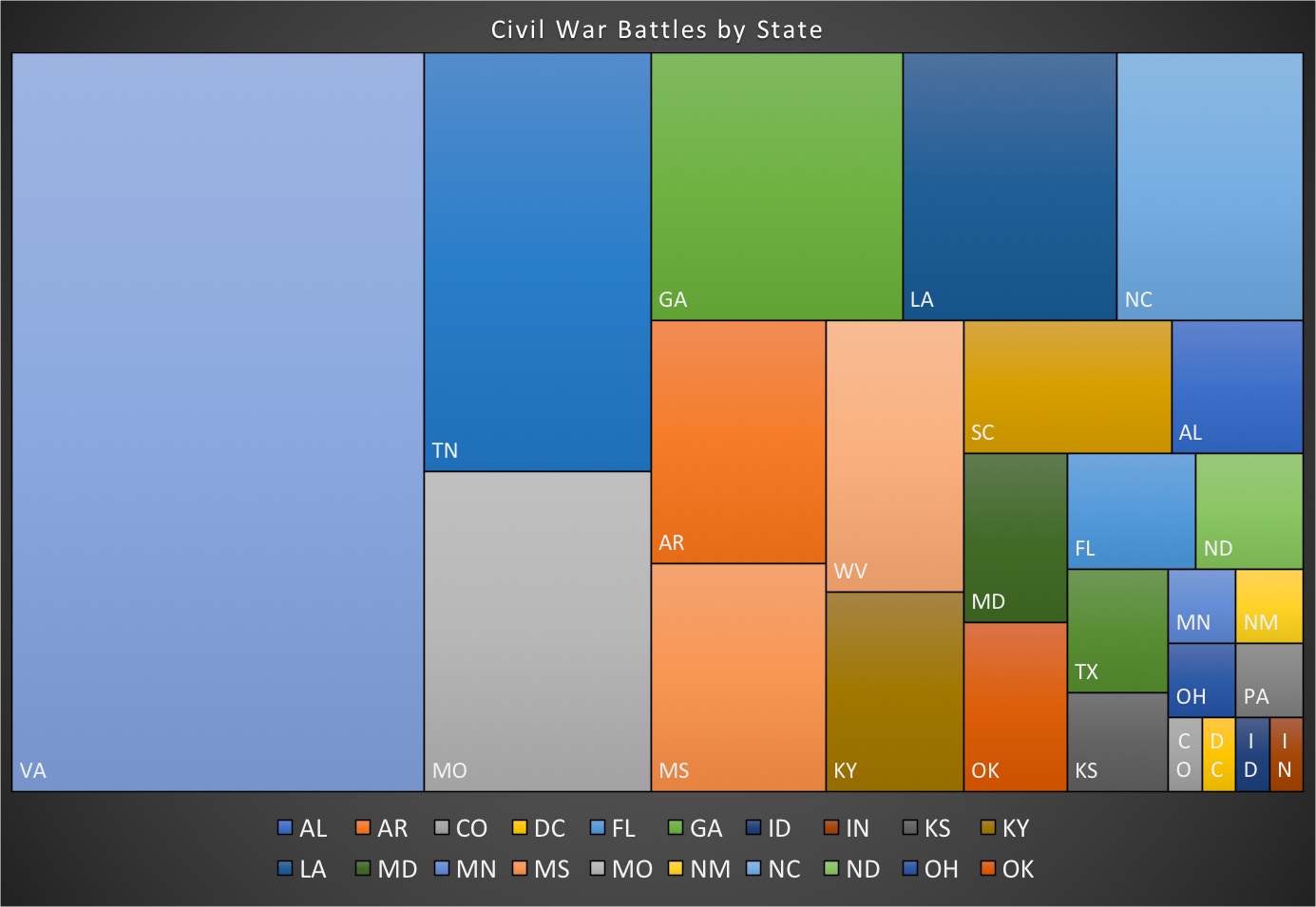

Richmond, Virginia, where one of the gun shows was being held on the same weekend as the DC march, would later become the capital of the short-lived Confederate States of America, arguably the largest-scale expression of Second Amendment rights. Virginia was home to 122 Civil War battles, five of which are among the bloodiest battles of the war. The Civil War – and the Mexican war before it – helped turn Colt, which invented “a revolver mechanism that enabled a gun to be fired multiple times without reloading” into a leading manufacturer of American firearms, albeit by supplying the Union. The company would start selling the AR-15 in 1964.

Enlarge

Gun tradition is part of the past and present; guns are almost worshiped as a recreational activity in the form of hunting and target shooting, a father-son bonding experience, a collectors’ hobby, necessary for safety, a record of history and, most of all, a way of life.

“At that time I had a very thick New York accent,” says Tringali of his arrival to the state, describing the culture clash. “…They looked at me like a transplanted Yankee. You know, because if you weren’t a good ol’ boy, you weren’t in there.”

He is certain that the ways of life, stereotypes and beliefs have implanted themselves as deep as the history grown and cultivated in the battlefields. As the journalists began walking away, adorned with their Midwestern accents, he shouted across the parking lot, “Be careful what you say, I’m serious.”

Dividing Line

However, Virginia itself is ripped apart by the gun divide that polarizes America, a state of changing demographics and political preference. You can find that dividing line, literally, in between Prince William and Fauquier counties. There are many gray areas to the realities, and, in some ways, to the debate. Stereotypes both exist, and they dissolve.

Prince William, which is influenced by the shadow of D.C., went for Hillary Clinton (as did the state), and Fauquier went for Donald Trump. The house next to the boundary between the counties flies both an American and confederate flag.

Enlarge

Prince William County is the face of a changing Virginia. The state was once reliably red, going back decades, changing only with the historic election of Barack Obama in 2008. The cosmopolitan nature of D.C. and Arlington has crept south. Many Manassas businesses and churches display signs in Spanish. Pentecostal church services in Spanish were occurring literally next to the Dominion Arms gun store, and there was a sign that refers to “halal.”

A Pakistani Muslim man sits behind the counter at the Days Inn hotel in Manassas, checking in a diverse array of guests. The man confides that, compared to Australia, his prior home, he doesn’t believe the United States is racist at all.

What Australia lacks in diversity, it makes up for in firearm safety, though. More than two decades ago, after a gruesome mass shooting, Australia introduced the National Firearms Agreement, which, according to the document, outlaws the sale and importation of automatic and semi-automatic weapons in License Categories C and D, requires a genuine reason for purchase, and enforces a waiting period of 28 days.

Enlarge

A brand new Manassas bar, La Tequila, is exceptionally quiet for a Saturday night, serving about a dozen people. Four friends walk in and head straight to the bar. The group, initially reluctant to share their opinions on gun control, admitted that they had all started shooting around 5-years-old. One, a very tall and muscular military man, talked extensively about using firearms for safety, security and sport. Wary of the media, they did not want their names used.

At the other end of the bar, a local was quick to lower his voice. He spoke just above a whisper, even in the bar setting. It was hard to hear him as he began to talk about how he knew he was unwelcome in this bar because he said that he was a gringo with a poor Spanish accent. The man said he wasn’t welcome because he didn’t speak Spanish, and even if he did, he would still be white. As people danced Salsa or played pool around him, the man said that everyone in the town carried a gun, and that not having one put you in more danger from gangs like MS-13.

He repeatedly emphasized that not only was it dangerous, but anyone here from out of town should watch their back. He continued by arching a brow as a group of El Salvadoran men walked through the door, causing the bartender to nod. Under his breath, he literally asked what one may think a group of guys like that were doing there.

President Trump has seized on these tensions. He has made MS-13’s inroads into Virginia a political sword to stem the state’s shift towards Democrats, especially as the central American gang members are sometimes undocumented immigrants. “Ralph Northam, who is running for Governor of Virginia, is fighting for the violent MS-13 killer gangs & sanctuary cities. Vote Ed Gillespie!” Trump tweeted in October 2017. Northam, the Democrat, won with just over 53 percent of the vote. Estimates since 2009 have put the number of MS-13 gang members in northern Virginia in the low thousands, although numbers vary. Some of their crimes are horrific and dominate the headlines.

Enlarge

Locals share that just a few months ago a body was found on the Fauquier-Prince William County line, and ended up being tied back to the MS-13.

One of the first landmarks on the quiet road into tiny Catlett is a Dollar General with its signature bright yellow sign. Two women, Michele Zuspan and Brenda Strawser, stood behind the counter helping a customer every few minutes. The pair says that the townspeople were sort of hoping authorities had found the body of a boy who has been missing for eight years but were saddened to hear it was different individual.

“My daughter won’t let her son even own toy guns, no need for it,” said Zuspan from behind the counter. “My son is 25,” said Strawser. “And he still has no interest in ‘em. He didn’t even like the toys as a kid.”

Although they don’t have any particular interest in guns, others do.

“We have a few regulars that open carry. They don’t come in everyday,” said Zuspan. “But they do come in.”

“This is a very gun place; this is a very rural place,” said Strawser.

The violence and reputation of the MS-13 leads to some stereotyping, said Zuspan and Strawser.

Racial tension in post-war Virginia is nothing new, of course. About 20 miles from Manassas sits Warrenton, Virginia, the sight of a ghastly lynching less than 20 years after the war.

Enlarge

Nathan Corder, an African-American who had eloped with the daughter of his white boss, was taken back to the county jail in Warrenton. A mob of around 75 masked men broke into the jail and dragged Corder by his neck to the cemetery over 200 yards away, and hanged him from a tree. An article at the time from the St. Louis Post Dispatch described the crowd as “proceeding as if in the execution of a solemn duty in, thus, avenging the violation of one of the most sacred unwritten laws of society.”

John Chew, a deacon at the predominantly black Walnut Grove Baptist Church in Warrenton, can trace his family in Manassas all the way back to the Civil War. According to Chew and his fellow deacon, Tony Bailey, in Virginia guns are just a part of life. Both men are African-American, and they are gun owners. Bailey was in the military for years before becoming a deacon.

Enlarge

“It is an amendment, it is a right, but you have to do your due diligence,” said Bailey.

Bailey sees where both sides of the debate are coming from, but as long as you are responsible, he has no problem with guns. And he sees them as a valuable part of self defense.

“The average citizen in Chicago, they can’t carry a gun, so criminals know they are easy targets,” said Bailey. “Where there is a will, there’s a way,”

The Walnut Grove Baptist Church, despite being miles away from the urban violence that is synonymous with places like D.C. and Chicago, cannot escape the shadow of gun violence. The deacons double as church security, and wear walkie talkies. They acted as though they were on guard and warily approached a reporter to inquire what he was doing there. The church recently underwent active shooter safety training through the Fauquier County Sheriff Department.

The men brought up the 2015 Charleston Church shooting at the Mother Emanuel Church, as well as the Sutherland Springs shooting in Texas. Dylann Roof, the Charleston shooter, held a long-running infatuation with the Confederate history and its flag, that same flag that can be seen being flown openly in Fauquier County.

Community gun show

Since Virginians had multiple options to choose from for gun shows that weekend, many of the vendors and visitors at the Manassas event were from the immediate area.

One could easily swap out the guns for something else, and the event would resemble any number of hobby fairs. At its core, the show is just a gathering place for members of the industry, collectors, history buffs, or the average enthusiast. This hobby convention just happens to house a Vietnam-era Jeep complete with machine gun, and the question of whether you have a gun with you at the door is just part of the routine, although of the journalism group, only the male student was asked.

Outside the show, visitors gather to eat BBQ or show off their new purchase. It is not an odd sight to see families with children together at the event; a young man asks for donations for a shooting camp scholarship for children at the door. Photos and videos are banned inside the facility.

Enlarge

Rick Nahas, the organizer of the show, seems to have a hardened distrust of media. In his mind, one has to know about the subject to report on it, and to him, the media don’t seem to know too much about guns. One of the other show organizers says a prominent news magazine once ran an old photo of him with a weapon next to a story about the gun used by the Virginia Tech killer, even though he had nothing to do with it.

“I’ve been thinking about this for a very long time,” says Nahas.

To Nahas, the cause of the gun violence issue is clear: Culture.

“In my mind, it’s gonna take two generations to get the culture away from the idea that it’s ok to kill people.”

“Humans aren’t talking to one another anymore,” he says, adding: “Look at these guys. You see anybody on a cell phone in here? Right now.”

He is right. No one’s on a cell phone. Visitors are kept occupied with rows of tables to look at, showcasing different specialties. Displays range from Civil War relics to weapons representing every side in World War II to top-of-the-line modern weapons. The gun collector community in Virginia is tight-knit. Beyond the guns, vendors and visitors alike catch up like old friends, whether outside the show at the concession stand or within the show, separated by a table crowded with firearms. There are tables of handguns and AR-15s for sale too. German war helmets and medals line some tables. Plastic bags of bullets go for $20.

“Guns just get attention because it’s, I don’t know, glamorous. It’s an easy way to kill people. It gives you distance, separation. You can’t do that with a knife. You can’t do that with your fist,” says Nahas.

Some aspects of the current mass shooter debate are clear as day to Nahas. But other aspects, less so.

“These school shootings have been committed by young males. White males. You tell me why, I don’t know,” he said.

For Nahas, it is an issue to be addressed in the home and in the doctor’s office. He thinks that anyone with mental health issues should be prohibited from purchasing firearms, at least until they are reassessed. He also attributes shootings at least partly to the modern home environment, seeing the current generation as disconnected from their parents. In other words, he finds the debate to be far more complex than firearms.

“I’m probably the last generation where I can say my mother stayed at home. My father worked. And when he came home, he ruled the roost. I don’t see that anymore,” he says.

Enlarge

But with the mass shooter debate, he can usually count on one thing. The usual blitz of media coverage and public debate, and then a return to the status quo.

“You heard about those [previous mass shootings, Vegas, Orlando], but you heard about ‘em, roughly a week and a half. And then it went [imitates snoring],” said Nahas. “Well, I’m trying to figure out why it’s getting so much mileage. I think it’s definitely the first time that students have actually spoken up.”

As the journalists walk through the gun show at the Prince William County Fairgrounds, noting an AR-15 priced at nearly $800, they recall sharp images of signs lining the sky, calling to remove the weapon from the shelves of stores and gun shows. That same gun has become the symbolic bogeyman, crossed out on signs and emblazoned on T-shirts. However, here, it’s just another weapon on a wall or table, offered for sale in a show that gives free admission to children.

Enlarge

Inside, rows upon rows of cases lined with weapons were packed into neat aisles, accompanying streams of firearm enthusiasts. A grizzled man with a Stonewall Jackson-esque face stood over a case of historic weapons, encouraging education.

“I have a model 1853 Enfield rifle, single shot,” Paul Goss said. “It’s an assault weapon because you can attach a bayonet to it. That is the definition of assault weapon.”

Enlarge

Goss and his young partner Christy Forman, two of many knowledgeable vendors at the event, sat behind a table and talked with guests about Confederate and Civil War history. They came prepared with living history photographs, battleground brochures, a gun from Gettysburg, and business cards.

There are over 325 million people living in the United States, all with an individual opinion about guns and gun violence. Some offer solutions like raising the age to purchase a firearm, ridding stores of toy guns, requiring universal background checks or psych evaluations, and more. Whether someone is pro-gun or anti-gun, Republican or Democrat, conservative or liberal, many say they believe there is a problem at hand. Although many people believe their opposition to be spouting “dumb BS,” many more are willing to start a real conversation. That’s also true here, at the Manassas gun show. Although people are steadfast in their support for the Second Amendment, many said they are willing to consider some change.

“There’s not a debate really,” Virginia Gun Collectors Association gun show vendor Mike Aslop said. “If both sides could sit down and talk, that would be great.”

Goss, a proud gun owner and member of the NRA, and Foreman are dissatisfied with media coverage of the gun debate. Although Goss thinks the March for Our Lives is senseless, he does not oppose raising the minimum age to purchase a gun, however.

“If they put more historians on the news, there would be a more rational discussion,” Forman said.

“You can’t discuss anything with anyone,” Goss said. “I’ve tried to.”

Straddling the divide

A Washington D.C. Lyft driver from Virginia sits, both literally and figuratively, at the intersection of the most controversial debate in the country, having witnessed extreme gun violence in his childhood and now owning a handgun. He straddles the divide. His opinions are nuanced.

Although some of his experiences are unique, the complexity of his views may not be, at least away from the pundits on cable news and the country’s corrosive political gridlock. A Pew Research study found that 44 percent of Americans know someone who was shot and three out of every 10 Americans owned a gun, with 36 percent who could be open to it. The study found that many gun owners tied gun ownership to personal freedom. The two Americas is also geographic. Almost half of rural adults own guns. “About half of white men (48%) say they own a gun. By comparison, about a quarter of white women and nonwhite men (24% each) own guns, along with 16% of nonwhite women,” the study concluded.

Elton Howard was seven years old when he was sitting in a car with his mother, her estranged husband, and his younger half-sister. Howard jumped out of the car when the man shot his mother five times. She survived.

Enlarge

“I’m pretty screwed up, but I think I maintain well,” Howard said. “I’ve been to therapy. I’m pretty resilient mentally, and I’m pretty aware of the damage.”

After experiencing gun-related trauma at such a young age, one might assume Howard avoids guns at all costs, but that’s not so. Today, Howard owns several firearms that sit in a bag at his house, some of which he purchased at The Nation’s Gun Show in Dulles, Virginia. The reason why? To create a better bond with his son.

According to Howard, it takes approximately 15 minutes to get a gun. Although Washington D.C. has some of the tightest gun regulations in the United States, he admits that people simply travel to areas with looser laws to purchase guns.

Despite being a gun owner, Howard says he believes both that the country is in dire need of stricter gun laws and a better understanding of mental health.

Even though Howard was able to cope with his gun violence experience and move on, it isn’t always easy for other survivors. For Randi Patregnani, the teenage girl standing outside the White House with the sign, every school day has become another reminder of the Valentine’s Day that brought Parkland national infamy and galvanized hundreds of thousands to join the Stoneman Douglas students in their march on Washington.

“I didn’t think I was going to make it out of there alive,” said Patregnani.

Every day, before school, Patregnani says that she hugs and kisses her mom goodbye, unsure if it will be her last time seeing her. She is still coming to terms with losing two of her best friends, Joaquin Oliver and Meadow Pollack.

“I still don’t believe it’s real, I still think I’m going to be in class, and Meadow is going to be there, and Joaquin is going to be there,” says Patregnani.

As Patregnani and her classmates from Parkland have demonstrated in the weeks since the shooting, they are determined to ensure that this time is different. For them, anything less than change is unacceptable.

“They can’t silence us. We will come down, we will talk to everyone and make this possible, because we are going to make a change,” says Patregnani. “We’re going to do it for them. Everything we do right now is for them. And for the future, and the people of the past.”