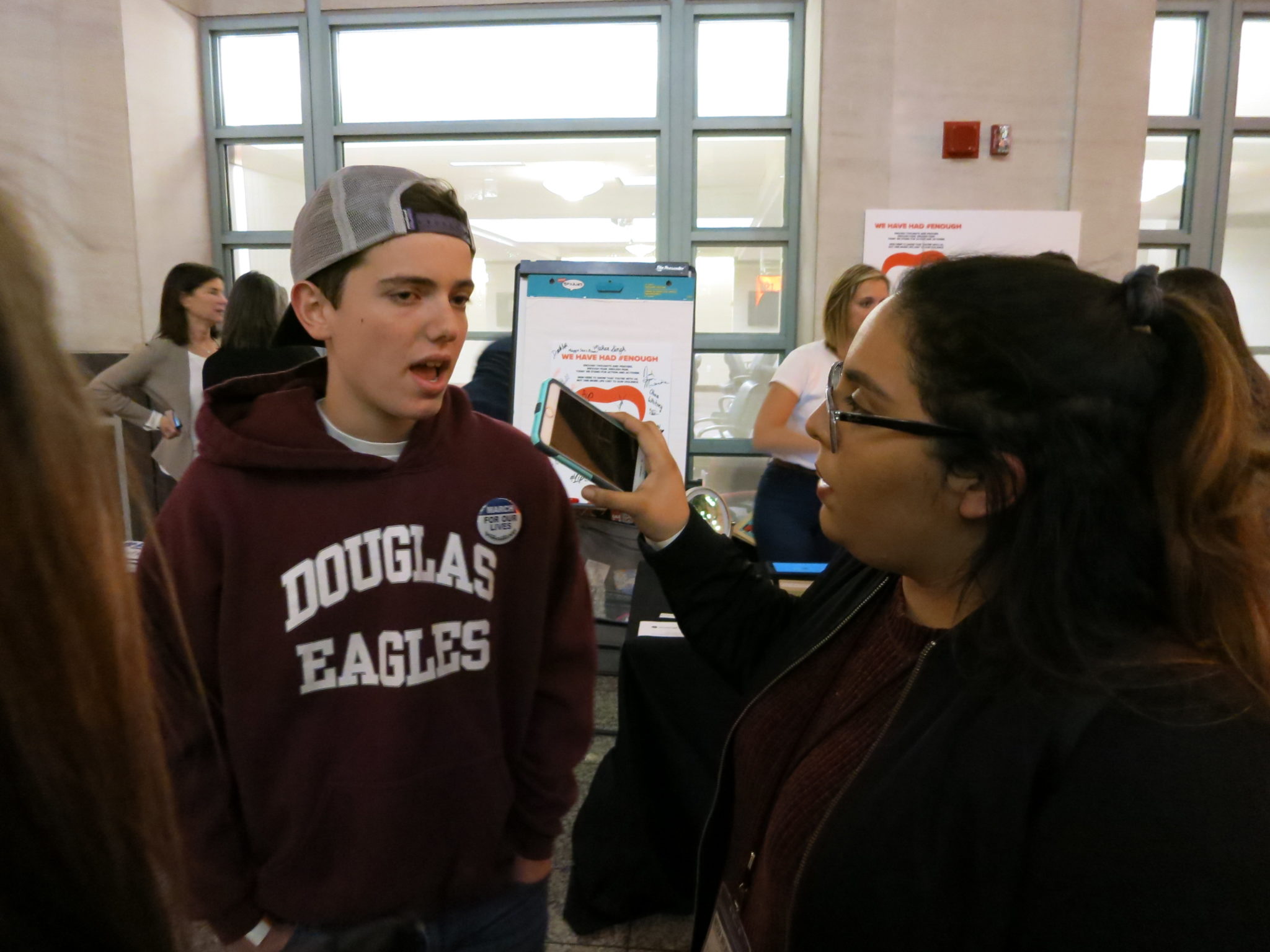

Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School student Drew Schwartz, 17, attended a poster- making event with his family at the National Education Association a day before the March for Our Lives march in Washington, D.C. Schwartz walked around the room while looking at the tables on display. He wore a burgundy sweatshirt that read “Douglas Eagles.”

“It means a lot to us,” Schwartz says, “It’s hard, but it definitely helps all of us to come together and march for something that brought us together, for a common cause.”

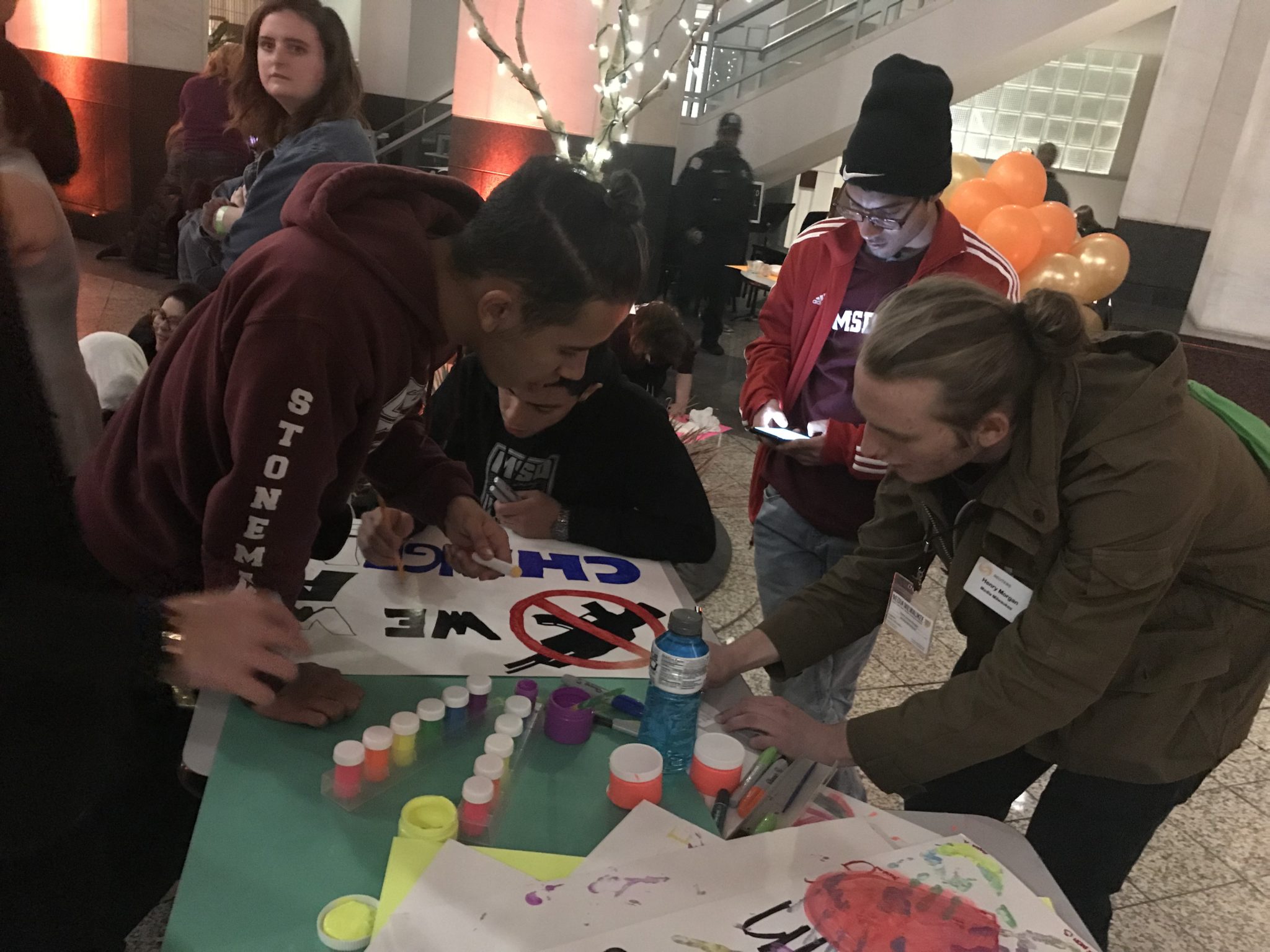

Students, families and others – many from Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School – came together to create signs the night before of the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C.

Enlarge

Schwartz paused to describe the horrors of that day. When the school announced that it was on a code red, Schwartz and other students ran to the nearest classrooms they could find. The high school’s procedure was for the teachers to turn off the lights and to find a spot that was far away enough from a window, where no one can see in. Schwartz was inside the high school when Nikolas Cruz started shooting. Though he wasn’t in the same building that Cruz was, he still hid for his life in a classroom and texted everyone he knew, letting them know that he was “okay.”

The shooting that happened in Stoneman Douglas high school left 17 students and staff members dead, some of whom Schwartz knew. He grew up with Meadow Pollack and Joaquin Oliver, who both died on what was one of the nation’s deadliest school shootings in its history.

“By doing this, somehow we give them justice,” Schwartz says. “They were well minded kids, they were really intelligent and spoke from the heart.”

Enlarge

At the event, Schwartz was accompanied by his mother, Robyn Schwartz. They live right behind the high school and, when she heard the sirens, she texted Drew immediately. She made a call to her friend who is a teacher, and the response she got was that there’s an active shooter in the building. Robyn made another call to her neighbor, telling him that he needed to take her to the high school.

“You got to get me up there. I am numb, and I need to get up there,” Robyn recalled that she said.

Robyn Schwartz was one of the first parents waiting outside the high school, along with her neighbor, who lost his daughter in the shooting. She watched as the youth started pouring out of the school; some of the students were injured, and others were covered in blood. She spotted some of her son’s friends; they went up to her and hugged her. They began to tell her that certain students were shot and had died.

“This guy is killing people,” Robyn says she realized.

Enlarge

Throughout the whole time, she texted back and forth with her son but couldn’t keep it together, and a friend of hers had to text for her. Robyn’s son kept texting her, “Am I safe? It is over? Did they get him? Are any of my friends dead?” She couldn’t say anything back because she kept receiving different responses from people about the shooter. At one point she told her son to play dead.

“It’s the worst nightmare a parent has to live through,” Robyn says. “I am blessed my kid came out.”

Robyn mentioned that the reason why Parkland shooting is different from Newtown, Columbine and Virginia Tech is because there wasn’t social media back then. But this time it’s different because of the age of the teenagers affected.

“They’re teenagers, not 5-year-olds; they’re young adults, they have a voice. That’s why it’s different,” Robyn says of the movement that has ignited.

As the night progresses, people are still coming in and out of the National Education Association building and creating more posters. In a table of only two people, Jessica Millete was creating a poster for the march even though she wouldn’t be able to attend.

Enlarge

“I figured, if I can’t be at the march, I might as well create stuff that can be represented at the march, to express how I feel about gun violence,” she said.

It makes Millete upset that people and politicians are telling the students to leave it up to the adults to fight for gun violence, especially when the students went through something traumatic. It upsets her even more that people and politicians, instead of protecting the kids and students, are shutting them down and trying to shut them up.

“How are the kids supposed to feel inspired to do these positions, when people who are older than them don’t believe that they are capable of thinking for themselves?” Millete says.

Former reporter for the National Education Association, Anita Merina, was among the crowd at the poster event showing her support for the students of Parkland. About 19 years ago, she marched in Washington D.C for the ‘Million Mom March;’ a march that was also for stricter gun control. Now, she is back with her twin sons, marching for the same issue. She has covered the Columbine, and Sandy Hook shootings; and that came with heartbreak because she saw all of it unfold.

“These students deserve, like my children, to be able to grow-up until they’re college seniors,” Merina says.

Enlarge

Merina sees that students are motivated to make a change, to take charge and to make a difference. She sees the students not stopping until something has changed and what she sees, she loves.

“I absolutely love it. I see the diversity of the students’ energy and the passion,” Merina says.

After seeing the country become divided, she believes that this march is unifying the country for the better. Gun-control, for her, is a topic that shouldn’t be pushed aside; it’s something that the country has to fix. Merina hopes that people feel the necessity to take action and to do something. For her, the fight doesn’t end with a march, it has to continue.

“People have to rise up and speak out. They have to change the laws for the better, otherwise people continue to die,” Merina says.